Gas and Electricity Markets | Domestic Production | Alternative Energy | Transparency | Recommendations | View in PDF

[wc_row] [wc_column size=”one-half” position=”first”] [wc_image attachment_id=”3286″ title=”Zoe Ripecky” alt=”Zoe Ripecky” caption=”” link_to=”” url=”” align=”left” size=”thumbnail”][/wc_image] Meet the Author Zoe Ripecky was a Fulbright Student Fellow in Ukraine in 2015–2016. She currently works at The Solar Foundation in Washington, DC. [/wc_column] [wc_column size=”one-half” position=”last”] [/wc_column] [/wc_row]Ukraine’s energy sector is simultaneously a cause for distress and hope. It represents both the country’s corrupt and vulnerable past, as well as its optimistic and proactive future. Reforms are underway to make Ukraine’s energy sector more competitive, efficient, and transparent, but well-meaning legislation is often slowed by low political will and entrenched business interests. Over the past few decades, the Ukrainian energy sector has been defined by heavy political influence, corruption, non-market based pricing, cross subsidization, and high operational losses. Ukraine is one of the least energy-efficient countries in the world, and its energy intensity[note]The ratio of Total Primary Energy Supply to GDP that is commonly used to measure energy efficiency[/note] is nearly ten times higher than the OECD average.[note]“Ukraine 2012: Energy Policies Beyond IEA Countries,” International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2012.[/note] This gross inefficiency has had a severe economic and environmental impact, with significant political implications. In 2012, Ukraine imported over 60% of its energy from Russia.[note]Ibid.[/note] Russia, and specifically its state-owned gas company Gazprom, used Ukraine’s dependence as a political weapon and threatened Ukraine with gas cutoffs and price increases. In 2006, 2008, and 2009, Russia shut off gas to Ukraine following westward political shifts by Kyiv. Ukraine’s vulnerability was only reinforced by domestic corruption and the capture of state-run energy companies by oligarchs. In Ukraine, a small number of well-connected individuals profited from this chaos and used price differences and subsidies to collect huge rents, robbing the state budget and contributing to a cycle of destruction.[note]Margarita Balmaceda, Energy Dependency, Politics and Corruption in the Former Soviet Union: Russia’s Power, Oligarch’s Profits and Ukraine’s Missing Energy Policy, 1995-2006, (Routledge, 2008).[/note]

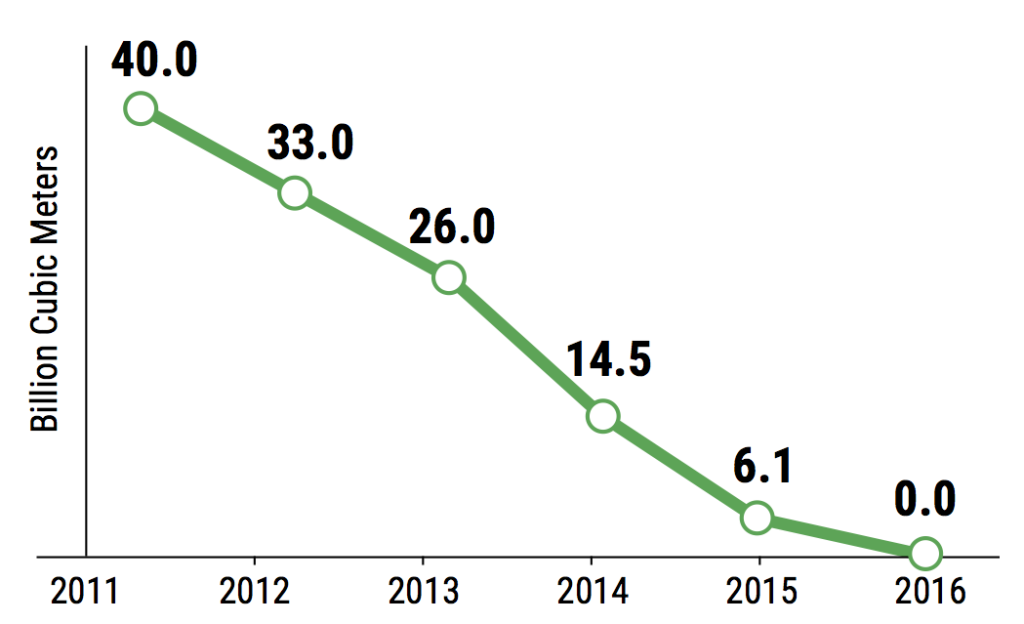

Regulatory problems, over-subsidization, and corruption have hindered the realization of this potential, but with successful reforms and a focus on efficiency, Ukraine could become primarily energy independent.On the other hand, in this time of change and pro-European orientation in Ukraine, the energy sector is a top reform priority and provides great hope for the future, despite historically gross mismanagement. Unleashing potential while simultaneously ensuring more efficient practices could transform not only Ukraine’s energy sector, but also its economy as a whole. Ukraine has a significant amount of oil and gas reserves, both conventional and unconventional, estimated at 9 billion tons of oil equivalent. Ukraine is ranked sixth in the world for hard coal reserves, though most of this is currently compromised in areas of the ongoing Donbas war.[note]“Eastern Europe, Caucasus, and Central Asia: Energy Policies Beyond IEA Countries,” International Energy Agency, 2015.[/note] According to the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) and Ukraine’s State Agency on Energy Efficiency and Energy Saving (SAEE), in 2015, the annual technically achievable energy potential of renewable energy sources was 68.6 million tons of oil equivalent per year, or enough to replace around half of Ukraine’s total annual energy consumption today.[note]“Renewable Energy Prospects for Ukraine,” International Renewable Energy Association background paper, April 2015.[/note] Regulatory problems, over-subsidization, and corruption have hindered the realization of this potential, but with successful reforms and a focus on efficiency, Ukraine could become primarily energy independent. In a move to prevent political influence exploit its energy vulnerability, Ukraine has also rapidly decreased direct gas imports from Russia, slowly decreasing the number down to zero last year (See Figure 1).[note]“Natural Gas Supplies to Ukraine 2008-2016,” Naftogaz, January 2017, http://naftogaz-europe.com/article/en/NaturalGasSuppliestoUkraine.[/note] [note]“Naftogaz Open Letter: A Year Without Gas Imports from Russia,” November 25, 2016, Naftogaz, http://www.naftogaz.com/www/3/nakweben.nsf/0/371FE97DD813E51FC225807600517667?OpenDocument&year=2016&month=11&nt=News&.[/note] [wc_center max_width=”500px” class=”” text_align=”center”]

Figure 1. Decrease in Gas Imports From the Russian Federation

Source: Naftogaz.

[/wc_center]

Energy reform is necessary for European integration and for meeting Ukraine’s commitments under the Energy Community treaty, signed by EU member states and several neighbor states in Southern and Eastern Europe. For Ukraine, meeting its treaty commitments will ensure more secure supplies and open up new investment opportunities. For Europe, integrating Ukraine into its internal market is a priority of its Energy Union strategy, in addition to being integral to its own energy security.

Figure 1. Decrease in Gas Imports From the Russian Federation

Source: Naftogaz.

[/wc_center]

Energy reform is necessary for European integration and for meeting Ukraine’s commitments under the Energy Community treaty, signed by EU member states and several neighbor states in Southern and Eastern Europe. For Ukraine, meeting its treaty commitments will ensure more secure supplies and open up new investment opportunities. For Europe, integrating Ukraine into its internal market is a priority of its Energy Union strategy, in addition to being integral to its own energy security.

If Ukraine is able to successfully topple the energy sector’s destructive cycle of corruption and dysfunction, broader reforms to Ukraine’s governance system and business climate will become all the more realistic.Under the Energy Community treaty, Ukraine must pass new laws that are aligned with EU-wide energy norms and legislation, notably the Third Energy Package. This legislative package, signed into EU law in 2009, liberalizes the EU’s internal gas and electricity markets through ownership unbundling and the establishment of an independent regulatory authority for each member state.[note]Ownership unbundling refers to the separation of production from supply operations. This is meant to prevent network operators from favoring their own energy production and supply companies.[/note] Meeting these standards is key to Ukraine’s Energy Community commitments, as well as to its EU Association Agreement.[note]“EU-Ukraine Association Agreement,” signed 21 March 2014, accessible at http://ukraine-eu.mfa.gov.ua/en/page/open/id/2900. [/note] Third Energy Package requirements must be in force before Ukraine can receive the full amount of the most recent EU macro financial assistance package (1.8 billion euros). Ukraine’s interests and the interests of its partners depend directly on the success of energy reforms. If Ukraine is able to successfully topple the energy sector’s destructive cycle of corruption and dysfunction, broader reforms to Ukraine’s governance system and business climate will become all the more realistic.

OPPORTUNITIES AND THREATS

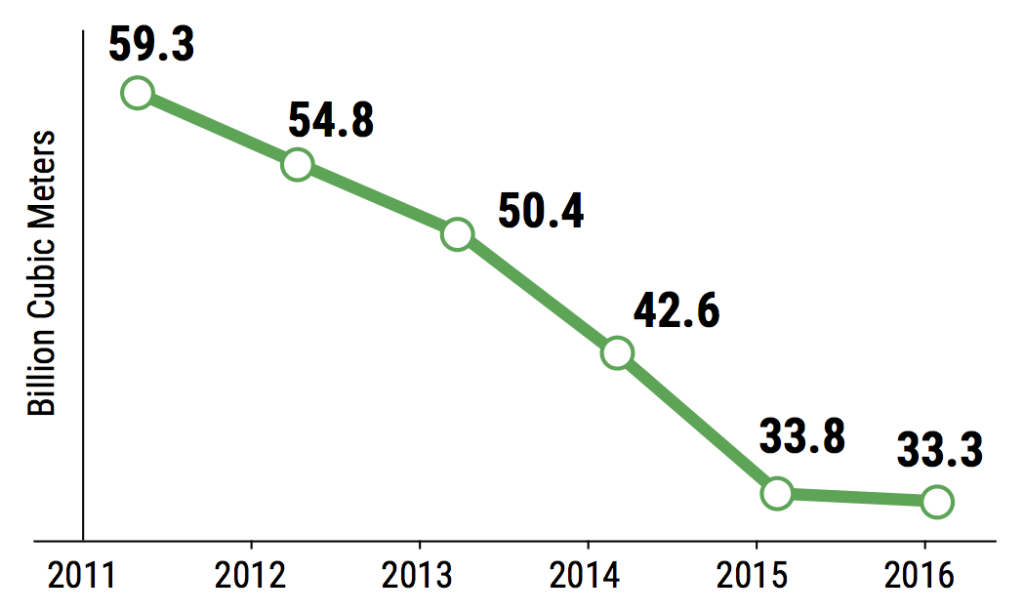

Gas and Electricity Markets

In April 2015, Ukraine’s parliament adopted a new law on restructuring the gas market in line with EU standards.[note]“Parliament Adopted Law ‘On Natural Gas Market,’” Press Service of the Ministry of Coal and Energy, 4 October 2016.[/note] However, incomplete secondary legislation has slowed this law’s implementation. Further, Ukraine’s state energy company, Naftogaz, and the Ministry of Energy have both created their own plans for the Naftogaz unbundling; conflicts between the two have delayed the process.[note]“Naftogaz Reorganization to Be Finished by April 2017,” Interfax, 26 November 2016.[/note] In a positive development, energy prices for households increased to nearly market prices over the past two years, almost entirely eliminating inefficiencies caused by the cross-subsidization of high industry prices with low household prices. Gas consumption has decreased heavily over the past five years, both as a result of the increase to market prices and the ongoing war’s effect on industry (see Figure 2).[note]Aslund Anders, “Securing Ukraine’s Energy Sector,” Atlantic Council, April 2016.[/note][note]“Natural Gas Supplies to Ukraine 2008-2016,” Naftogaz, January 2017.[/note] The electricity sector also has seen significant progress on reforms. In June 2016, the Ukrainian government submitted a Third-Energy-Package–compliant Electricity Market draft law to Parliament, which was adopted on its first reading in September 2016.[note]“Government Approves a Bill to Demonopolize Electricity Market,” Information and Communication Department of the Secretariat of the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine, 3 February 2016.[/note] Some have expressed hope that gas sector reform will set a precedent for the electricity market, but both processes have been moving at too slow a pace. [wc_center max_width=”500px” class=”” text_align=”center”] Figure 2. Ukraine’s Decreasing Gas Consumption

Source: Naftogaz.

[/wc_center]

An Independent Regulator

A draft law establishing an independent energy regulatory committee (NEURC), necessary for EU integration and the next IMF macro financial tranche, has been drafted with the participation of a multitude of actors.[note]This body is analogous to the Federal Energy Regulatory Committee in the U.S.[/note] The goal of a reformed NEURC is to provide accountability and predictability to attract private investment and to ensure efficient, competitive, and secure energy supplies. A strategic group comprising Ukrainian experts, members of parliament, and international consultants produced a draft in line with European standards. In September 2016, this bill was adopted by Parliament and passed into law. Legally, this new regulatory committee is independent from political and market forces. The committee receives its funding from fees paid by energy market participants, and members are paid salaries that are average for the industry (unlike other public servants who are paid much less, incentivizing corruption). Two members of the committee are nominated by the president, two by Parliament, and one by the Ministry of Energy. As of its last announcement in November 2016, the European Secretariat is in the process of assessing whether the law complies with the Third Energy Package.[note]“Ukraine Regulatory Authority,” Energy Community, November 2016, https://www.energy-community.org/portal/page/portal/ENC_HOME/AREAS_OF_WORK/Implementation/Ukraine/Regulatory_Authority[/note]

Figure 2. Ukraine’s Decreasing Gas Consumption

Source: Naftogaz.

[/wc_center]

An Independent Regulator

A draft law establishing an independent energy regulatory committee (NEURC), necessary for EU integration and the next IMF macro financial tranche, has been drafted with the participation of a multitude of actors.[note]This body is analogous to the Federal Energy Regulatory Committee in the U.S.[/note] The goal of a reformed NEURC is to provide accountability and predictability to attract private investment and to ensure efficient, competitive, and secure energy supplies. A strategic group comprising Ukrainian experts, members of parliament, and international consultants produced a draft in line with European standards. In September 2016, this bill was adopted by Parliament and passed into law. Legally, this new regulatory committee is independent from political and market forces. The committee receives its funding from fees paid by energy market participants, and members are paid salaries that are average for the industry (unlike other public servants who are paid much less, incentivizing corruption). Two members of the committee are nominated by the president, two by Parliament, and one by the Ministry of Energy. As of its last announcement in November 2016, the European Secretariat is in the process of assessing whether the law complies with the Third Energy Package.[note]“Ukraine Regulatory Authority,” Energy Community, November 2016, https://www.energy-community.org/portal/page/portal/ENC_HOME/AREAS_OF_WORK/Implementation/Ukraine/Regulatory_Authority[/note]

Domestic Production and Energy Efficiency

Despite sizable domestic energy potential, Ukraine is primarily considered a transit country, and reforms are meant to secure this role. However, as mentioned above, Ukraine has sizable untapped energy resources. Unfortunately, investment in Ukraine’s upstream sector is still considered risky by external investors and even internal companies. Oleg Prokhorenko, CEO of Ukraine’s largest gas producing company, UkrGasVydobuvannya, wrote an op-ed in the Kyiv Post detailing corruption schemes as major obstacles to reform in this area.[note]Oleh Prokhorenko, “Corruption Threatens State Gas Producer,” Kyiv Post, 17 March 2016.[/note] Efforts for greater energy efficiency, often considered the “cheapest” energy source, are also less than satisfactory. Last year, the government issued “warm loans” to homeowners looking to weatherize their homes. The program was extremely popular, and demand for loans exceeded funds available. However, as of today, the government budget does not detail funds for continuing the program.[note]Dmytro Naumenko, “Why It Is Important to Keep the Heating Loans Program,” Kyiv Post, 11 December 2016. [/note] Aside from this program and adoption of the “National Energy Efficiency Action Plan until 2020,” and other non-binding actions, little concrete movement has been made in this area. The EU, World Bank, and other institutions have focused on energy efficiency in some of their efforts in Ukraine, but more can be done in this instrumental area.Alternative Energy

Ukraine has large potential alternative energy production. According to the International Renewable Energy Association, Ukraine has enough renewable energy potential (solar, hydro, wind, biomass, and geothermal) to fulfill half of its energy needs today. In 2013, the Cabinet of Ministers adopted a document called “The Energy Strategy of Ukraine Through 2030,” prioritizing renewable energy because of its contribution to energy security and lack of environmental consequences. This policy sets ambitious goals for renewable energy, including a doubling of the share of renewable energy in the power sector from 6.9% in 2010 to 11.4% in 2030.Powerful forces behind traditional fuels have hampered political will for strong enforceable renewable energy policies.In a symbolically significant announcement, Ukraine’s Ministry of the Environment recently unveiled plans to transform Chernobyl, the radioactive site of the 1986 nuclear disaster, into a large site for solar energy. The 1000-square-mile exclusion zone is uninhabitable, which makes sunlight “one of the only things that can be harvested.”[note]Anna Hirtenstein , “Chernobyl’s Atomic Wasteland May Be Reborn with Solar Energy,” Bloomberg, 26 July 2016.[/note] In November 2016, two Chinese solar firms unveiled plans to take on this project.[note]David Stanway, “Chinese Solar Firm to Build Plant in Chernobyl Exclusion Zone,” Reuters, 21 November 2016.[/note] Although the potential is large and the stated goals are ambitious, powerful forces behind traditional fuels have hampered political will for strong enforceable renewable energy policies. Ukraine also requires outside investment and guidance in this area, which has not yet been present.

Transparency and Efforts of Civil Society

Ukraine is a candidate country of the Extractive Industry Transparency Initiative (EITI), a global standard used to promote transparency in resource extraction around the world.[note]“UAEITI,” EITI Ukraine, https://eiti.org/implementing_country/26[/note] Late last year, Ukraine published its first EITI report on its oil and gas sectors.[note]“Ukraine disclosed data on payments in oil and gas production for the first time,” Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative, 12 October 2015. [/note] The purpose of the report is to disclose information about how much companies pay the government for the extraction of resources, and how much the government receives from them. Since resources are a public good, this strategy ensures that extractive industry taxes and royalties are fairly and transparently paid and accounted for in the government budget. In Ukraine, many hope EITI will serve as a foundation for continued reforms to establish transparency and open competition, and set a standard by which all actors in the sector play. The Ukrainian Government also passed a new law, “On Strengthening the Transparency of Extractive Industries in Ukraine,” that imposed new standards for transparency in the Energy Sector in line with EITI requirements.[note]“Ukraine to Implement EITI,” CMS-LawNow.com, 11 July 2015.[/note] The Energy Reforms Coalition, a coalition of energy sector-minded civil society groups, are lobbying for reforms, monitoring progress, and ensuring open information in the process.[note]“US Ambassador expects Ukrainian government to carry out energy sector reform in 2016,” Energetic Reforms, enref.org, 11 December 2016.[/note] Both of these developments were huge victories for Ukrainian civil society, which worked closely with government and business to complete the report and strongly lobbied to pass the law.RECCOMENDATIONS

- The U.S. Congress should appropriate the funds designated for support of Ukraine’s energy sector. In 2014 Congress passed the Ukraine Freedom Support Act which authorized the appropriation of $50,000,000 in support of projects that increase Ukraine’s energy production and efficiency (Section 7, Subsection C). Appropriated funds could play a key role in Ukraine’s economic development and Europe’s energy security.

- The U.S. should increase cooperation with civil society groups that specifically focus on the energy sector. As in all sectors in Ukraine, civil society has completed the brunt of the work of monitoring and enforcing reforms as well as cooperating with international entities related to the energy sector. The U.S. should focus support on groups that understand the situation and provide concrete solutions with goals of making the energy sector more transparent, efficient, and competitive.

- The U.S. should condition aid on concrete progress. Support from the U.S. is integral to reforms in the energy sector, so in many ways the U.S. is in a position to expect results. Support and aid should be tied to concrete reforms that are in line with European standards and contribute to the goal of creating a more competitive, transparent, and efficient energy sector. This includes fully implementing a new independent regulator, as well as new laws reforming the gas and electricity markets.

- The U.S. should prioritize Support for Domestic Production, Alternative Energy and Energy Efficiency. The U.S. should offer assistance and strategic funding to make Ukraine more energy efficient and less reliant on imports. Focus on efficiency and domestic production could significantly decrease Ukraine’s demand as well as the political vulnerabilities that come along with it. Plans to assist with alternative energy development and production should also be mobilized, as part of a U.S. interest in a secure, economically viable, and sustainable Ukraine.

- Take a harder stance against Gazprom. Russia has used Gazprom as a tool for political manipulation and threats, and the U.S. should impose more stringent sanctions targeting Gazprom. The company’s actions have negatively affected Ukraine for decades, and are a direct threat to European stability. Gazprom has been continuously tied to corruption, political influence, and violation of EU competition laws.

- Aslund, Anders. Ukraine: What Went Wrong and How to Fix It, “Chapter 10: Cleaning Up the Energy Sector,” Peterson Institute for International Economic, April 15, 2015.

- Balmaceda, Margarita, Energy Dependency, Politics and Corruption in the Former Soviet Union: Russia’s Power, Oligarchs’ Profits and Ukraine’s Missing Energy Policy, 1995-2006. Routledge, 2008.

- Balmaceda Margarita, The Politics of Energy Dependency: Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania Between Domestic Oligarchs and Russian Pressure, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2013.