What Can be Done? | What Has Changed? | What Has Been Done? | Conclusions and Recommendations | View in PDF

[wc_row] [wc_column size=”two-third” position=”first”] [wc_image attachment_id=”3456″ title=”Ilone Sologub” alt=”Ilona Sologub” caption=”” link_to=”” url=”” align=”left” size=”thumbnail”][/wc_image] Meet the AuthorIlona Sologub is a Senior Economist at Kyiv School of Economics. Ilona has experience in developing and implementing of market risk models and preparing analytics on various topics including Ukrainian and world economy, science, politics and market research.

[/wc_column] [wc_column size=”one-third” position=”last”] [/wc_column] [/wc_row]Ukraine suffers from systemic corruption and can be characterized as a captured state.[note]Bohdan Vitvitsky explains the sources of systemic corruption in Ukraine and possible strategies for its reduction in “Corruption in Ukraine: What Needs to Be Understood, and What Needs to Be Done?” VoxUkraine, 5 June 2015.[/note] Although corruption does exist in the private sector, public sector corruption draws the most attention and requires state action. This paper uses the World Bank’s narrow definition of corruption — “the abuse of public office for private gain.”[note]Thomas de Waal, “Fighting a Culture of Corruption in Ukraine,” Carnegie Europe, 18 April 2016. See also the World Bank Group’s “Helping Countries Combat Corruption: The Role of the World Bank,” section on Corruption and Economic Development.[/note]

In a captured state, the majority of government employees use their positions to serve their private interests rather than the interests of the state or its citizens. Of course, there are no corruption-free states. But in countries with only episodic corruption, the majority of public servants act honestly, often because the expected punishment for rent-seeking activities exceeds their benefits.

A modern state performs several important functions, including providing public goods, correcting market failures, protecting competition, partially redistributing income and setting up a social safety net. In captured states, these functions are performed badly — public goods are scarce and low-quality, regulations are used for the enrichment of officials and their “friends,” markets are monopolized (often with the help of administrative barriers to entry), and usually there are high levels of inequality, with super-rich elites, a thin middle class, and a low-income majority. Moreover, inequality refers not only to income but also to opportunity. For example, children of low-income families have very low chances to enter a good university (because their parents cannot afford good schooling or private lessons). Another example of inequality is how difficult it is for “outsiders” to enter government service, let alone take on key positions. In Ukraine, this situation has only partially changed after the Revolution of Dignity, due to the overwhelming inertia within the system.

A thriving shadow economy is both a consequence and a source of corruption. First, regulations are difficult to comply with due to their contradictory nature or vagueness, and thus officials can decide what constitutes compliance and collect bribes from businesses willing to escape prosecution for non-compliance. Therefore, firms are pushed into the shadows in order to (1) circumvent some regulations and (2) get some unregistered cash for bribes. Second, corruption at the highest levels of government serves as an excuse for corruption at all levels. A government clerk may think, “Why can I not accept this small gift if the president has built a palace for himself?” Under systemic corruption, honest actors are a minority since honest behavior is punished by the system: government officials get low salaries; moreover, they are often required to regularly pass cash to higher-level officials, which makes taking bribes a necessity.

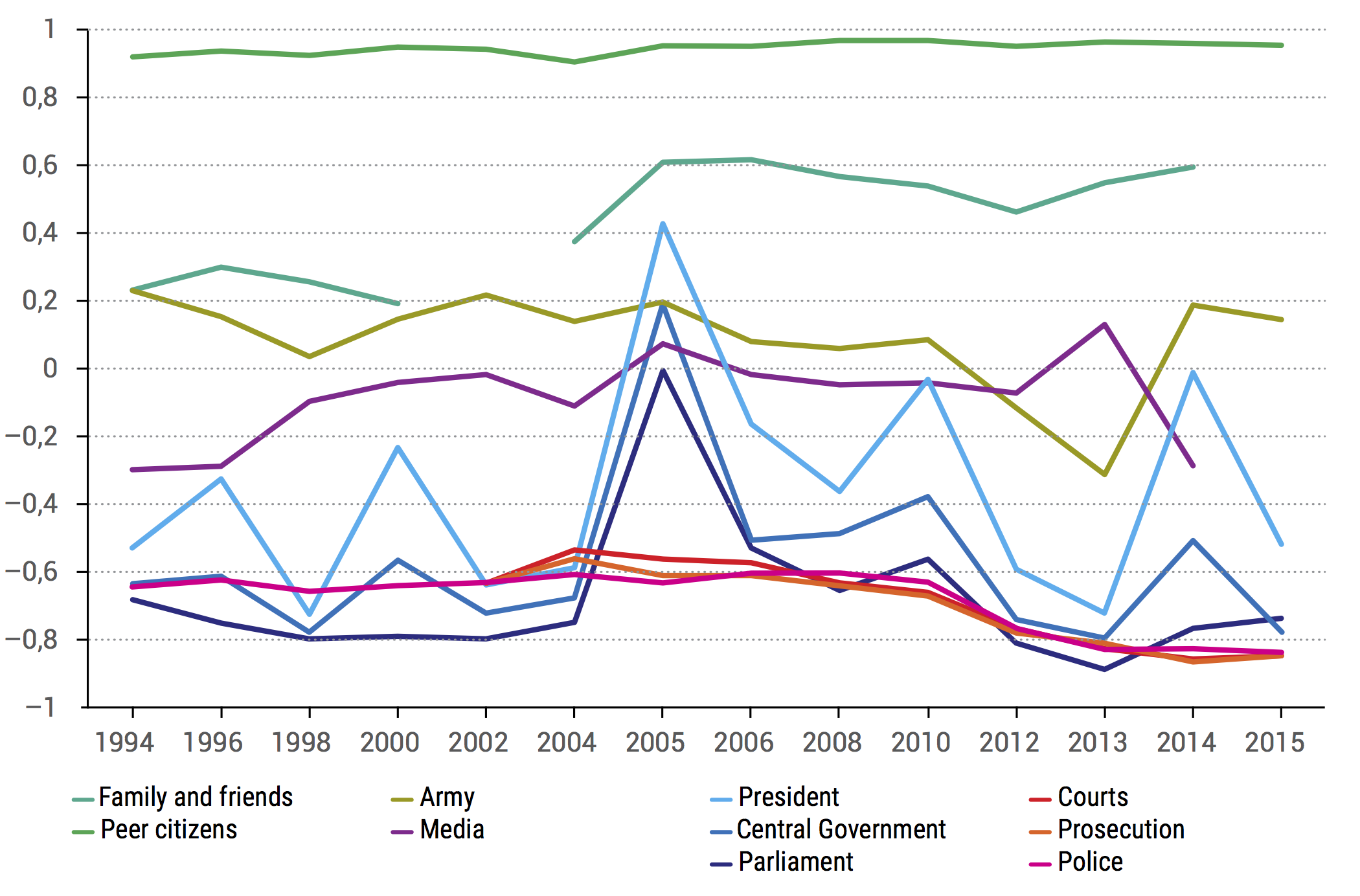

Citizens of systemically corrupt countries generally have low trust in state institutions. Figure 1 illustrates this for Ukraine. This lack of trust slows down even genuine attempts at reforms.

Figure 1: Level of trust to different institutions. Data source: Institute of Sociology “Social Monitoring Survey”[note]See, for example, the electronic library of the National Institute for Sociology, accessible at i-soc.com.ua/institute/el_library.php.[/note]

Figure 1: Level of trust to different institutions. Data source: Institute of Sociology “Social Monitoring Survey”[note]See, for example, the electronic library of the National Institute for Sociology, accessible at i-soc.com.ua/institute/el_library.php.[/note]

Figure 1 shows the index of trust measured from –1.0 to 1.0, which is constructed in the following way: the share of people who do not trust or mostly do not trust a certain entity is subtracted from the share of people who trust or mostly trust this entity, and the result is normalized by the share of people who provided an answer other than “hard to say.” A negative index means that more people do not trust an institution than trust it. This figure shows that Ukrainians trust each other but do not trust political institutions (indices of trust in the President, Parliament and government are negative), but the lowest trust is to the “militsia” (police) and judicial system.

The Ukrainian system of corruption has its roots in the pervasive regulation of the Soviet period, during which two “systems” operated in parallel: official state structures and deals made on a person-to-person level. Indeed, relying on informal arrangements was the only way for citizens to survive. This informal system continued to develop during the years of independence, and now it is so well established that many see corruption as an inherent feature, or “mentality,” of Ukrainians. In a recent survey by the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology (hereafter referred to as KIIS), 66% of respondents agree that “Bribery is an integral part of the Ukrainian mentality.”[note]The report “Corruption in Ukraine” was prepared by Kyiv International Institute of Sociology and financed by UNITER project of the United States Agency for International Development. It can be accessed at kiis.com.ua/materials/pr/20161602_corruption/Corruption%20in%20Ukraine%202015%20ENG.pdf[/note]

The Ukrainian system of corruption has its roots in the pervasive regulation of the Soviet period, during which two “systems” operated in parallel: official state structures and deals made on a person-to-person level

We believe that this “mentality” stems from two factors: (1) excessive and complicated regulations and (2) a large, poorly paid, and inefficient bureaucracy that uses its monopolistic position for rent-seeking. By the end of 2013, every government agency was a rent-seeking machine delivering payments from the bottom up, with each level taking a share. There is evidence that people paid to get even a low-salary job at the government or a state-financed institution to become a part of this machine.[note]This infographic texty.org.ua/action/file/download?file_guid=37483? shows cases of bribes which had been proven in the courts. For example, a nurse at a district hospital paid $1000 to get her job which pays less than $100 a month. The highest proven bribe ($200k) was paid for the position of a head of regional ecology inspection. There is also anecdotal evidence that highest level positions are sold for millions of dollars.[/note]

Therefore, it is not surprising that not only “oligarchs” but also mid-level bureaucrats strongly resist reform attempts. Ukraine has close to 300,000 civil servants and nearly 3 million public employees.[note]State Statistical Service, 2015, ibid.[/note] On the other hand, millions of citizens engage in the supply side of corruption, paying bribes and using personal connections to “get things done” (bypass the law) or to accelerate bureaucratic procedures.

Legislation in Ukraine is often complicated and contradictory, sometimes deliberately designed to create opportunities for rent-seeking, either by providing discretion to officials, by imposing very high compliance costs on businesses, or both.

The KIIS report shows that 70.7% of Ukrainians had some experience with corruption in 2015, compared to 72.4% in 2011. This small but statistically significant reduction is due to a decrease in the incidence of voluntary bribes from 40.5% in 2011 to 35.6% in 2015.

At the same time, the level of extortion (i.e., involuntary bribes, payments demanded by officials) is much higher than the incidence of voluntary bribes. Extortion has remained relatively stable with 56.8% of the population experiencing extortion in 2015, compared to 57.1% in 2011.[note]Ibid.[/note]

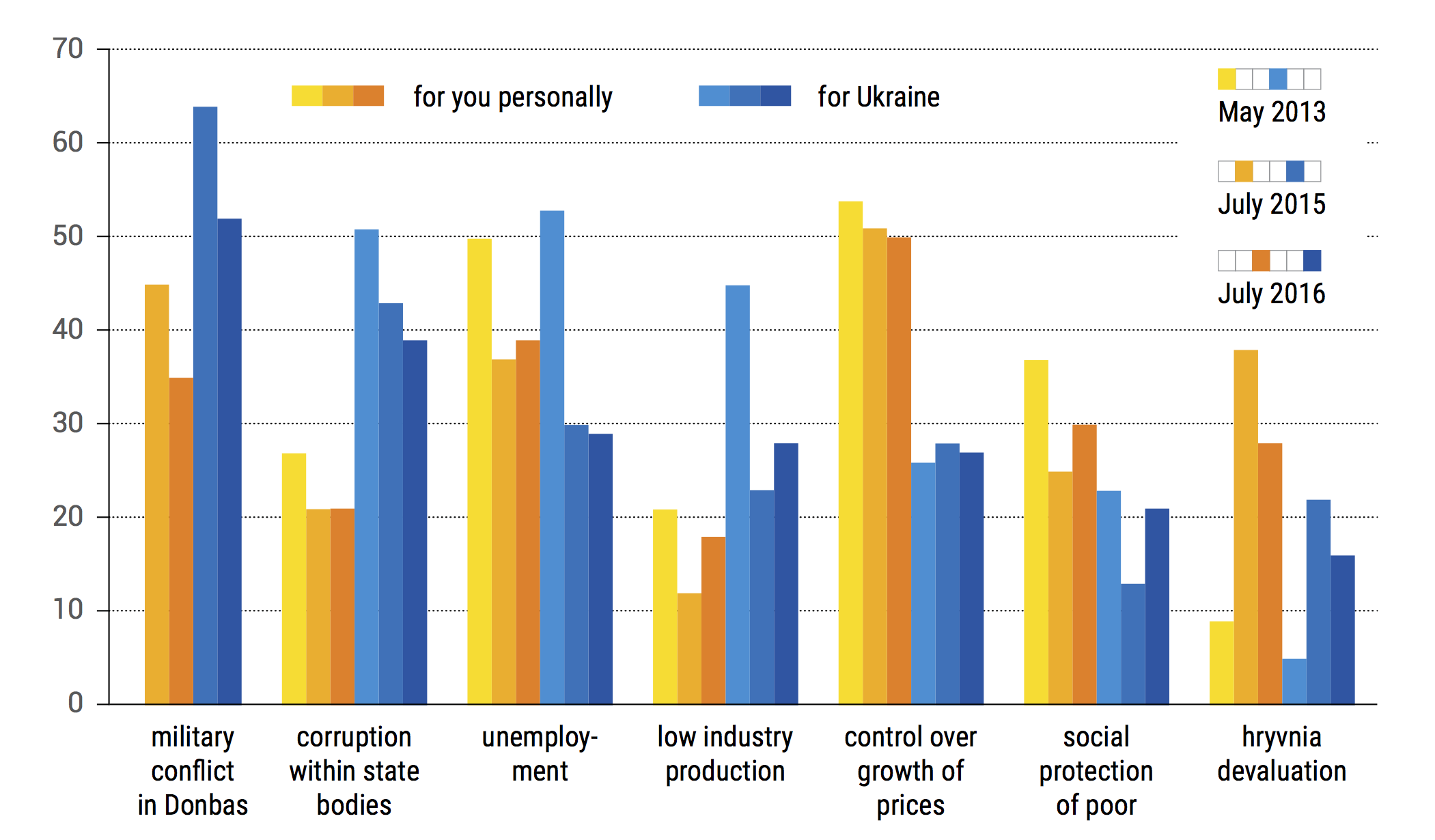

The majority of people recognize corruption as one of the most important problems of Ukraine (figure 2).

Figure 2: The most important problems for Ukraine and personally for respondents, who could pick up to three answers. Data source: IRI surveys for different years[note]Public Opinion Survey Residents of Ukraine, International Republican Institute. Three IRI dated 14–28 May 2013, July 16–30 July 2015, and 28 May – 14 June 2016.[/note]

Figure 2: The most important problems for Ukraine and personally for respondents, who could pick up to three answers. Data source: IRI surveys for different years[note]Public Opinion Survey Residents of Ukraine, International Republican Institute. Three IRI dated 14–28 May 2013, July 16–30 July 2015, and 28 May – 14 June 2016.[/note]

WHAT CAN BE DONE?

Anti-corruption reforms require not only political will but a strong legal foundation. This is especially true in Ukraine, where strict compliance with legislation is often used as a form of sabotage. Therefore, “cleaning” the legislation from vague or contradictory norms would greatly reduce the opportunities for corruption.[note]Although this factor is rarely mentioned, Ukrainian labor legislation, which is overly protective of employees, is slowing down reforms considerably. For example, there were multiple instances when corrupt state-owned enterprise heads could not be fired because they were on extended sick leave or vacation. When replaced by new people, who selected through open competition, the corrupt officials were reinstated by courts on technicalities. There are also many instances when police officers did not pass the integrity check and were subsequently fired, only to be reinstated through court decisions because of a loophole in the law on the police reform. For an interesting comparison to the relationship between reform and labor legislation in Botswana, see Joseph Patrick Ganahl, Corruption, Good Governance, and the African State. A Critical Analysis of the Political-Economic Foundations of Corruption in Sub-Saharan Africa (Potsdam University Press, 2013).[/note]

Among the post-Soviet countries, the only success story in meaningfully reducing corruption is Georgia.[note]Dismantling systemic corruption is rarely a success and requires strong political will from top officials and/or some external incentive. For example, Ganahl (2013) shows that in Sub-Saharan Africa only Botswana has been a success. Ganahl, Joseph Patrick (2013). Corruption, Good Governance, and the African State. A Critical Analysis of the Political-Economic Foundations of Corruption in Sub-Saharan Africa. Potsdam University Press, 2013. https://publishup.uni-potsdam.de/opus4-ubp/frontdoor/index/index/docId/6664/. Eastern European countries are a good example of tackling corruption but they had a large stimulus in the form of EU admission, and some of them considerably reduced AC effort afterwards – see Mungiu-Pippidi, Alina (2010). The Experience of Civil Society as an Anticorruption Actor in East Central Europe. Romanian Academic Society and Hertie School of Governance, 2010 [/note] Several veterans of Georgian transformation, including its former president, Mikheil Saakashvili, had taken high-level positions in Ukraine after the Maidan. However, by December 2016 all of them resigned. Faced with a strong resistance from the mid-level bureaucracy and a lack of political support from top-level officials, these reformers have shown only moderate progress.

By looking more closely at the Georgian example, we can identify a few key ingredients to the success of its reforms, nearly all of which are missing in Ukraine.

- Outsiders. In Georgia, reforms were implemented by political “outsiders” (i.e. those outside the political system), whereas the current Ukrainian political elite has been entrenched for decades. While many figures from the private sector or other countries entered the previous government led by Arseniy Yatsenyuk, they lacked strong political support and were not able to overcome the resistance of the system. To a certain extent, the much needed high-level political support for reforms was provided by the IMF, EU and international organizations, who played the role of an “outside enforcer of reforms.”[note]The 2015 IMF/Ukraine Memorandum can be found at imf.org/external/np/loi/2016/ukr/090116.pdf. For a discussion of its implementation, see Olena Bilan, et al., “Ukraine’s Homework: IMF Program Review Results and New Tasks,” VoxUkraine, 21 September 2015.[/note]

- Concentration of power and a mandate for reform. In Georgia, there was one decision-making center, the government under President Saakashvili. In Ukraine there are effectively two heads of the executive power — the President and the Prime Minister — who are often involved in infighting. In the current political cycle, this led to a sharp drop in their popular support and replacement of the Prime Minister in April 2016.[note]Roger Myerson, Gerard Roland and Tymofiy Mylovanov, “A Case for Constitutional Reform in Ukraine,” VoxUkraine, 13 April 2016. See also slide 21 of IRI’s May-June 2016 public opinion survey, which can be accessed at iri.org/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/2016-07-08_ukraine_poll_shows_skepticism_glimmer_of_hope.pdf.[/note] An alternative to this infighting is power concentration, but this too carries concrete risks.

- Small country and a small state. Another obvious difference between Ukraine and Georgia is the size of the country and the size of the state. In Georgia at the start of reforms in 2003, total government expenditure was 16.5% of GDP. It peaked at 36% in 2009.[note]For the last few years Georgia has been keeping government expenditures below constitutionally prescribed 30% of GDP level.[/note] In Ukraine, which has ten times the population of Georgia, the government redistributed 37% of GDP in 2003, and 45% in 2014.[note]Data from the IMF World Economic Outlook Database, April 2016.[/note] Naturally, the larger the “pie” that officials get to distribute, the higher is the potential for corruption, especially given the high level of discretion that Ukrainian legislation provides.

- External conditions. The global economic and security situation during the time of intense reforms in Georgia (2004-2007) was more favorable than today, so the results of reforms were quickly visible in the form of economic growth and foreign direct investment (FDI) inflow. Today, Ukraine cannot expect similar economic growth even if it instituted similarly radical reforms. On the other hand, the economic crisis may provide additional incentives for structural changes.

- The war. Russian aggression in Ukraine started before the reform process, when the state was practically dysfunctional. While the war mobilizes both civil society and the government, it detracts resources from productive activities — in 2016, Ukraine’s defense expenses were 2.7% of GDP compared to 1% of GDP in 2013. [note]Data from the Ukrainian treasury.[/note] Sometimes the war is used as an excuse for the sluggishness of reform efforts while creating additional opportunities for corruption, such as non transparent procurement of military supplies.

WHAT HAS CHANGED?

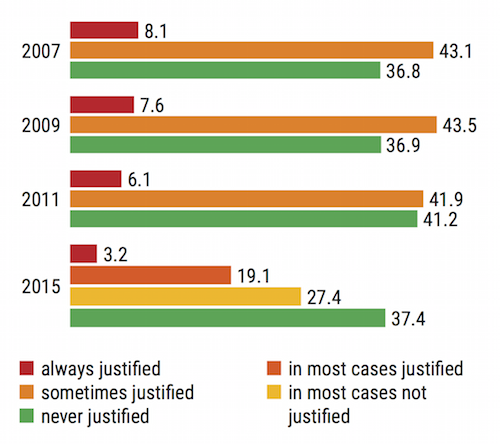

People’s attitudes in Ukraine toward corruption have shifted. While we cannot directly compare the data from the 2011 and 2015 surveys by the Ukraine National Initiatives to Enhance Reforms (UNITER, see Table 1), we note a two-fold decrease in the share of people who think that corruption for personal benefit is always justified.

Figure 3. Do you believe that giving bribes, unofficial services or gratuities can be justified if it is necessary for resolving a problem that is important for you? (% of respondents), Source: UNITER surveys.[note]Data for 2007, 2009, 2011 are derived from the UNITER corruption report found at

Figure 3. Do you believe that giving bribes, unofficial services or gratuities can be justified if it is necessary for resolving a problem that is important for you? (% of respondents), Source: UNITER surveys.[note]Data for 2007, 2009, 2011 are derived from the UNITER corruption report found at

www.uniter.org.ua/upload/files/PDF_files/Publications/corruption_in_ukraine_2007-2009_2011_engl.pdf. Data for 2015 are derived from the UNITER corruption survey found at www.uniter.org.ua/upload/files/PDF_files/Anticorr-survey-2015/CorruptionFULL_2015_Eng_for%20public.pdf[/note]

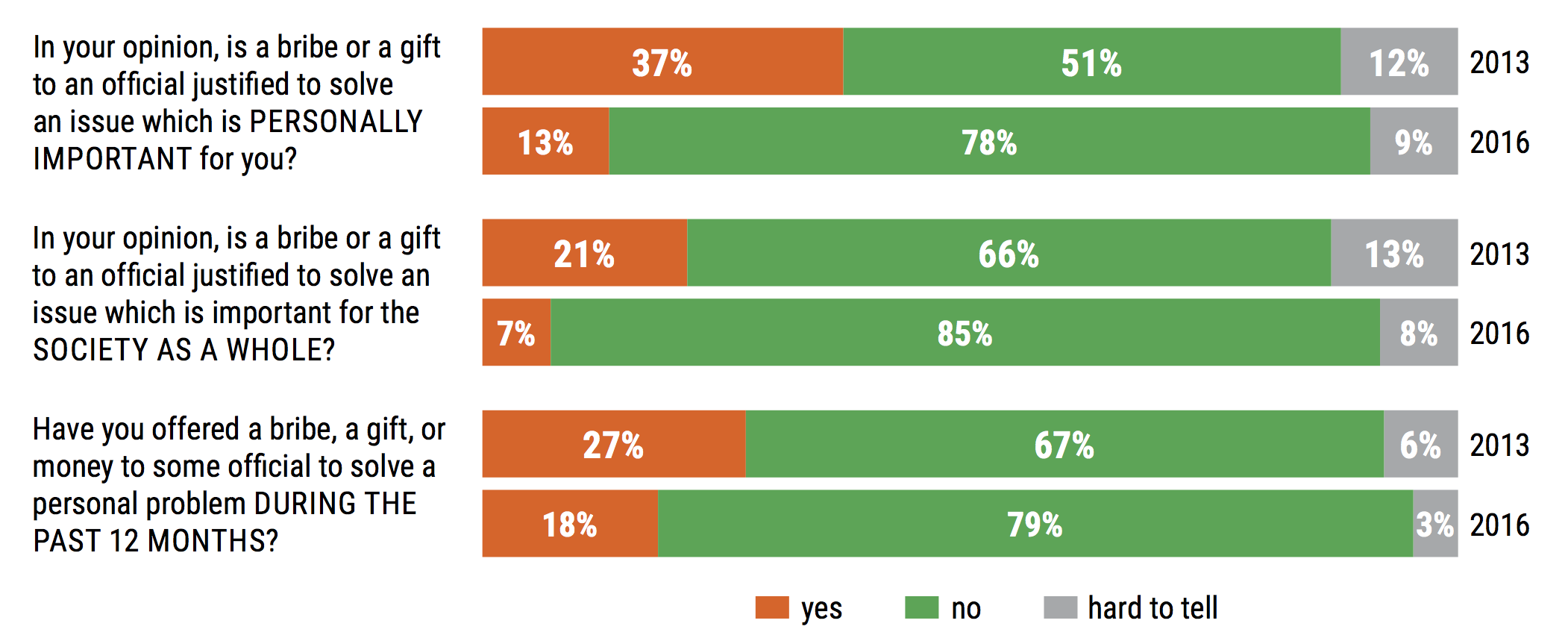

Another survey provides more evidence of decreased tolerance to, as well as incidence of, corruption (Figure 3). At the beginning of 2016, three times fewer people thought that corruption could be justified, and the share of people who offered some benefit to an official decreased by a third compared to 2013.

Figure 4. Change in tolerance to corruption and incidence of corruption. Source: Rating Group survey.[note]Rating Group Ukraine, “Electoral and Social Moods of the Population,” 4 February 2016, ratinggroup.ua/en/research/ukraine/elektoralnye_i_obschestvennye_nastroeniya_naseleniya.html, specifically slides 30–31.[/note]

Figure 4. Change in tolerance to corruption and incidence of corruption. Source: Rating Group survey.[note]Rating Group Ukraine, “Electoral and Social Moods of the Population,” 4 February 2016, ratinggroup.ua/en/research/ukraine/elektoralnye_i_obschestvennye_nastroeniya_naseleniya.html, specifically slides 30–31.[/note]

WHAT HAS BEEN DONE?

Reduction of corruption rests on two pillars – prevention and punishment. In our view, prevention is more important since in the absence of opportunity, a corruption act will not occur. However, with a focus on punishment, the probability of corruption is nonzero, depending instead on the scale of the corruption benefit and the expected punishment. Therefore, reforms which reduce the possible scope of corruption are more efficient than measures aimed at punishing corrupt officials.

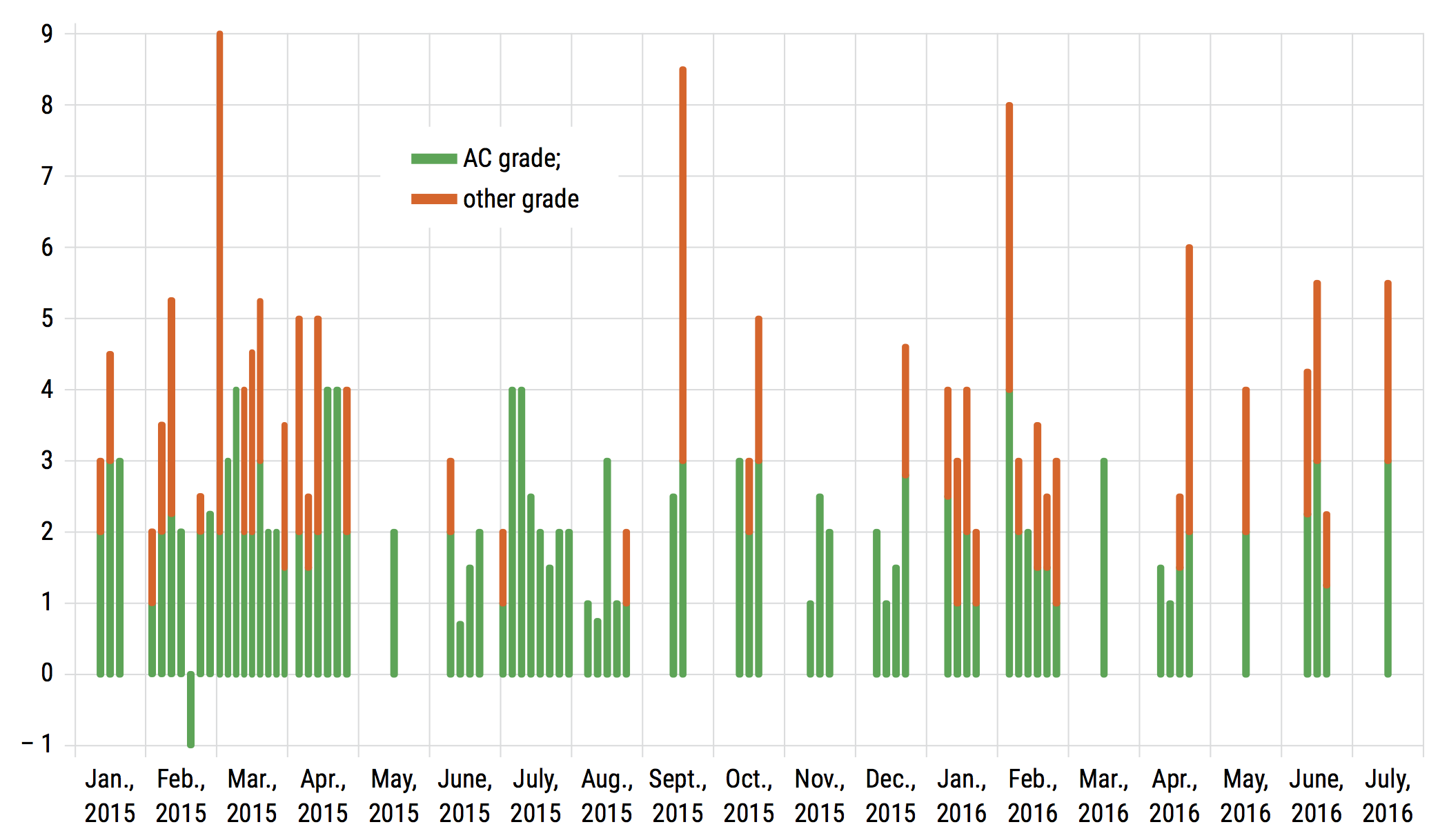

Figure 4 shows that many reforms adopted in 2015-2016 contained anti-corruption components, although very few of them were purely anti-corruption measures.

Figure 5. Legislative changes related to anti-corruption, expert grades; a) anticorruption; b) deregulation

Figure 5. Legislative changes related to anti-corruption, expert grades; a) anticorruption; b) deregulation

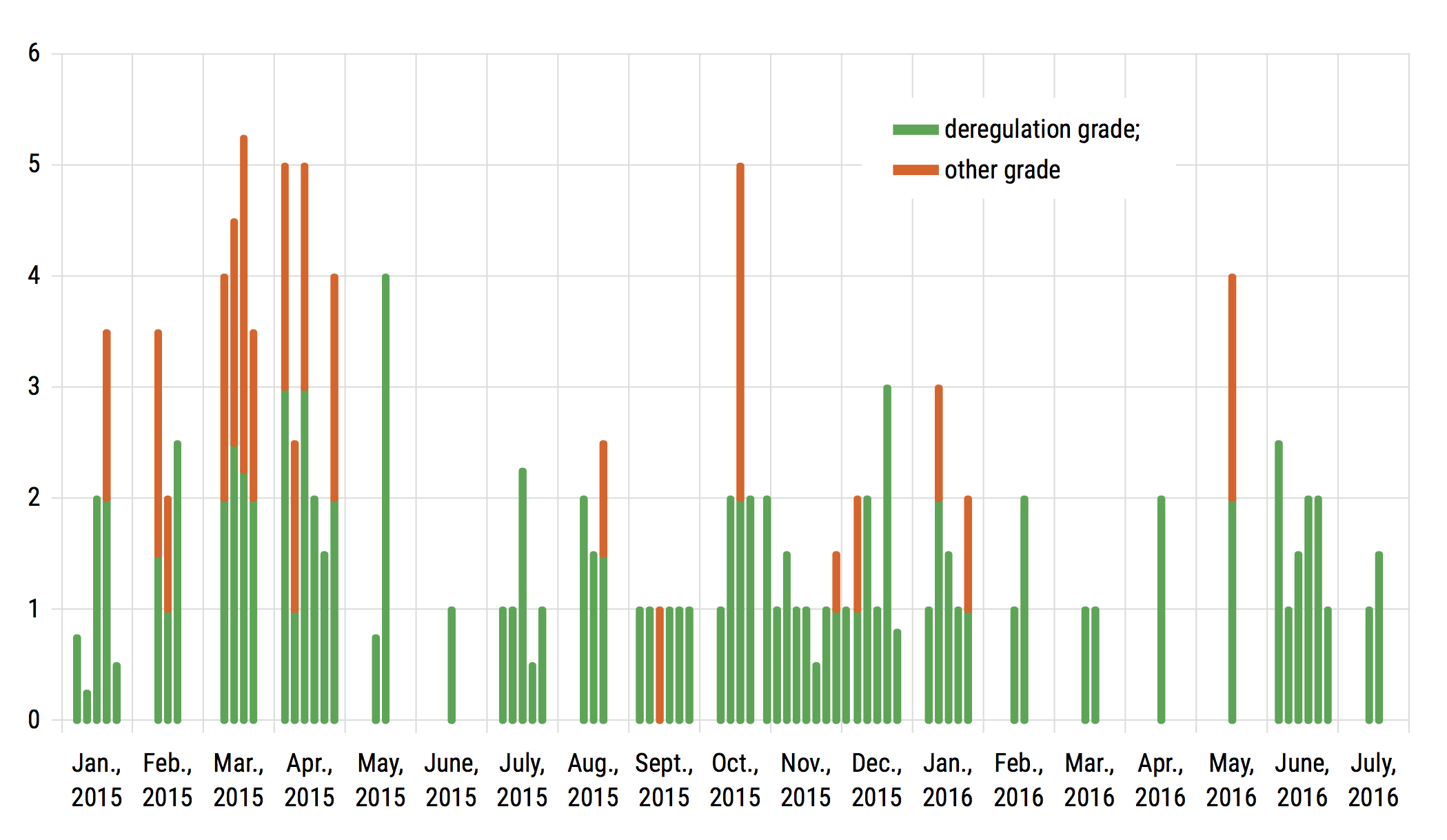

Source: VoxUkraine Index for Monitoring of reforms (IMORE) data. The index is an expert evaluation of legislative changes by their expected impact.[note]For detailed information about the methodology behind calculating the index, see imorevox.in.ua/?page_id=30[/note] Each legislative change can fall in one or several of five index components – Governance and Anti-Corruption, Public Finance and Labour Market, Monetary Policy and Financial Markets, Industrial Organization and Foreign Trade, Energy Independence. Within each component a legislative change is graded from –5.0 to 5.0 depending on its significance and expected impact.

Below we provide an overview of the main developments that reduce the opportunities for corruption in Ukraine.

State procurement reform is one of the most important reform Ukraine has passed. Since August 1, 2016, the Prozorro electronic public procurement system has been mandatory for use by all state agencies and budget-financed institutions. Developed by a group of civil activists who now work for the Ministry of Economic Development and Trade, this system has recently won the Procurement Leader Award.[note]“Prozorro — The Best System in the World in the Sphere of Public Procurement,” Transparency International, 19 May 2016.[/note] To date, the use of the system saved about UAH 7 billion ($280 million).[note]See the Ministry of Economic Development FB page: facebook.com/mineconomdev/posts/1160370977353882[/note] Prior to its introduction, only firms with personal relationships to government officials could expect to win tenders (and naturally, their price was not the lowest one), so “outsiders” did not even submit their bids.

An important part of the procurement reform was the outsourcing of state procurement of medical drugs to international organizations. The law implementing this reform was adopted in March 2015 and enacted in late 2015, but it has already brought in savings of about $34 million.[note]See the report and infographics here: patients.org.ua/2016/07/07/mizhnarodni-organizatsiyi-zakuplyat-na-zekonomleni-200-mln-grn-dodatkovi-liki/[/note]

Unification of gas prices (elimination of cross-subsidization of households at the expense of industry) and de-monopolization of the natural gas market have wiped out a wide range of opportunities for corruption. For example, gas distribution companies were able to buy subsidized natural gas intended “for the population” and sell it to industry with more than a 100% markup.

As a result, the deficit of the state-owned energy monopoly Naftogaz dropped from above 7% of GDP in 2014 to about 2% of GDP in 2015, and it is expected to be zero at the end of 2016.[note]Andrei Kirilenko, “Ukraine: Strategic considerations,” VoxUkraine, 17 September 2014.[/note] Bringing prices for households to import parity level was a necessary precondition for natural gas market reform. The next step was the adoption of the law “On natural gas market” that introduced some elements of the EU Energy III package. Starting in April 2017, Ukraine’s gas market is expected to function in accordance with EU norms. Equally important has been the replacement by the EU of Russia as Ukraine’s main gas supplier.[note]The replacement of Russia as Ukraine’s primary gas supplier is important because gas supplies were used by Russia as a weapon, and for quite a long time for the extraction of rents by the Russian and Ukrainian governments.[/note] In addition, Ukraine launched a large-scale energy efficiency program supported by the World Bank.[note]“District Heating Energy Efficiency,” Projects and Operations, World Bank, 2016.[/note]

Unification of gas prices and de-monopolization of the natural gas market have wiped out a wide range of opportunities for corruption

About 100 deregulation initiatives have been adopted during 2015-2016, although the majority of them were incremental (Figure 5). The most important ones are the laws on deregulation, canceling of a number of licenses and certificates or simplifying procedures for obtaining them. Deregulation results in large savings for business. For example, the former Minister of Agrarian Policy said in an interview that simplification of obtaining quarantine certificates alone saved the industry about UAH 12 billion ($0.5 billion) per year.[note]Oleksiy Pavlenko, “Олексій Павленко: Моя мета, щоб до кінця 2016 року в Мінагропроді було нуль державних підприємств.” Agropolit.com, 11 February 2016.[/note] The recent simplification of registration procedures for drugs certified in the EU, U.S., Canada, and Japan should make informal payments to accelerate the registration unnecessary and thus reduce the prices of these drugs. Regulatory cost analysis is now being introduced into the state agencies since March 2016 (before that officials who drafted regulations rarely considered the fact that regulation bears some cost both for business and the state).

Figure 6. Legislative changes related to deregulation. Data source: Index for Monitoring Reforms (IMORE) by VoxUkraine.

Figure 6. Legislative changes related to deregulation. Data source: Index for Monitoring Reforms (IMORE) by VoxUkraine.

At the beginning of 2015, the Ukrainian government launched a Business Ombudsman office[note]Business Ombudsman Council, https://boi.org.ua[/note] financed by the OECD. For just over a year, the office considered over a thousand complaints from businesses about government agencies and issued seven systemic reports addressing specific regulatory problems and providing policy advice for the government.

Recently, 360 government decrees containing outdated regulatory norms were cancelled. That said, deregulation is not proceeding as fast as expected, and action plans are often behind the schedule.[note]According to the reports of the State Regulatory Service: www.dkrp.gov.ua/info/5273[/note]

Banking sector reform has been aimed at improving the overall health of the banking system by strengthening macroprudential regulation, reducing related lending, and increasing the responsibility of banks’ owners. These reforms led to the large-scale elimination of “zombie banks” and money-laundering institutions, making it harder to hide and legalize dubious funds. This reform is one of the most successful.

Transparency and elements of e-government. The Ministry of Justice introduced an online service in early 2015 and opened about 300 data registries, among them real estate and car registries. Additionally, online portals with budget data and transactions[note]See www.e-data.gov.ua.[/note] of budget-financed institutions as well as with data collected from government agencies[note]See www.data.gov.ua.[/note] were created. Currently they are operating in testing mode.

Anti-corruption civil society organizations and activists indicate that the use of “open data” has greatly simplified their watchdog activities.[note] Surveyed by VoxUkraine within the study “Incentives and constraints for Civil Society Organizations to effectively engage in anti-corruption reforms at national and regional levels,” which was supported by the Ukraine National Initiatives to Enhance Reforms (UNITER) program, implemented by Pact, and made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). A total of 63 anti-corruption civil society organizations and activists were interviewed.[/note] More registries are expected to open, and they will be integrated with the Prozorro e-procurement system.

Low salaries of government employees are partly responsible for corruption because they reduce the “foregone salary” portion of expected punishment.

State service reform is currently being implemented through the new law “On Civil Service,” enacted in May 2016. The law introduces more transparency into recruitment and functioning of government agencies and allows for increases in the salaries of officials. Low salaries of government employees are partly responsible for corruption because they reduce the “foregone salary” portion of expected punishment. Proper selection and proper remuneration of state officials should increase their quality and integrity.

Judicial reform — on which the implementation and enforcement of many other kinds of reforms depend — has just started. The amendments to the Constitution and two laws reforming the judicial system adopted in August 2016 are aimed at enhancing the independence of the judiciary and increasing its quality.[note]Details of the judicial reform as well as a discussion of its possible caveats can be found here imorevox.in.ua/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/IMoRe-report2016_07_03_ENG.pdf and here imorevox.in.ua/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/IMoRe-report2016_07_17_ENG.pdf[/note] During the first half of 2016, the High Qualification Commission — an independent body evaluating the integrity of judges — evaluated over 300 judges (about 4% of the total number). Progress is slow but steady. Here, there is a tradeoff between the speed of reform and independence of the judicial system.

So far, one of the few successes in the sphere of law enforcement has been the introduction of the new patrol police, using the material and expert support of U.S., Canadian, and Japanese governments. The transformation of the investigative police is under way. As of September 2016, integrity checks of police officers have been completed in 7 out of 26 regions, resulting in the firing of 14% of the screened personnel.[note]See the National Reform Council report for the first half of 2016, available at reforms.in.ua/sites/default/files/upload/reform-report-1h-2016.pdf[/note]

The most notorious law enforcement body is the Prosecution Office (PO), which is constitutionally under the influence of the President and thus can be used to pressure his or her opponents. Presidents Poroshenko’s unwillingness to have an independent prosecutor general has harmed his international image.[note]For example, in September 2015 the U.S.Ambassador to Ukraine Geoffrey Pyatt made a number of strong statements about Viktor Shokin, the prosecutor general at that time. Geoffrey R. Pyatt, “Corrupt prosecutors under Shokin ‘are making things worse by openly and aggressively undermining reform,’” Kyiv Post, 26 September 2015.[/note] The National Anti-Corruption Bureau (NABU) recently began investigating some prosecutors.[note]Roman Romaniuk, “On the Threshold of War: The Prosecutor general’s Office and the National Anti-Corruption Bureau,” Ukrainska Pravda, 11 August 2016.[/note] The prosecution office retaliated by searching NABU premises and detaining some of its staff, harming its own credibility and that of its recently appointed new head.

State-owned enterprise (SOE) reform and privatization have faced high resistance at all levels of the government. There have been some positive achievements, such as the regular publication of balance sheet data of the 100 largest SOEs, adoption of the law that prescribes creation of supervisory boards at SOEs and the replacement of the management of the largest enterprises (such as the state gas extraction company UkrGazVydobuvannia, state railway company UkrZaliznytsia, and others).[note]According to the former Minister of Economic development, SOE losses in 2014 amounted to over UAH 80 billion (5.7% of GDP) while in 2015 they fell to UAH 16 billion (0.8% of GDP). Certainly, not all of these losses can be attributed to corruption but based on the anecdotal evidence, a large part of them can. See, for example, http://ukranews.com/ua/news/406693-zbytky-derzhkompaniy-u-2015-stanovyly-16-mlrd-gryven.[/note] However, competitive selection processes for CEO positions at state enterprises are often sabotaged, and frequently the “old” heads are renewed in their positions by courts.

State-owned enterprise reform and privatization have faced high resistance at all levels of the government.

Although privatization was unblocked in March 2016, it so far has been a failure.[note]According to Treasury reports, for the first 9months of 2016, UAH 77 million of the planned 17.1 billion were obtained from privatization (which is not, however, very different from the previous few years). 80% of the planned privatization revenues had to arrive from the sale of the Odesa petrochemical plant. In 2015, actual privatization revenues were less than 1% of the plan.[/note] For example, the Ukrainian government botched the sale of the Odesa Petrochemical Plant, large seen as a key privatization litmus test.[note]Basil Kalymon, “Memo to Ukrainian Government: Privatization Can Succeed if You Get Out of the Way,” Atlantic Council’s New Atlanticist, 9 August 2016.[/note]

From the discussion above, it is clear that changes that have the most adverse impact on corruption are related to corruption only indirectly. However, a number of specific anti-corruption initiatives have been introduced as well.

Most notably, a number of specialized anti-corruption bodies have been created.

The National Anti-Corruption Bureau (NABU) became fully operational in early 2016, and as of September 2016 it had opened 245 investigation cases. Only 34 of them have been processed through the courts.[note]Dmytro Shymkiv and the National Reforms Council, “Reforms Progress Monitoring,” September 2016.[/note] The NABU has hired 506 of the planned 700 employees.[note]NABU official report: ukurier.gov.ua/media/documents/2016/08/09/10_p11-13.pdf [/note] However, NABU cannot work at full capacity since Parliament is reluctant to adopt the law that would allow NABU to have independent surveillance service.[note]Currently, NABU can wiretap someone’s phone, for example, only via the Ukrainian Security Service, which increases the risk of leakage of information on its investigations.[/note] A Specialized Anti-Corruption Prosecutor Office (SAP) supports the NABU activities, and now employs about half of the planned 45 people.

NABU became fully operational in early 2016, and as of September 2016 it had opened 245 investigation cases. Only 34 of them have been processed through the courts.

The creation of the National Agency for Corruption Prevention (NACP) to collect, process, and publish electronic declarations of officials and political parties has not gone smoothly.[note]Details on the process and challenges of e-declaration system creation here: antac.org.ua/en/publications/e-declarations-of-public-officials-final-countdown-or-new-battles-ahead/[/note] In April 2016, after almost a year of delay, the NACP was finally launched, and the electronic declarations system was launched on September 1, 2016 despite multiple attempts to disrupt it. Both Ukrainian public[note]An influential media – European Pravda – editorial calling to delay visa-free regime and IMF tranche for Ukraine until proper e-declaration system is in place. See “Reforms Imitators. Why the West Should Deny Poroshenko Financial Aid and Visa Free Travel,” European Pravda, 15 August 2016.[/note] and international partners[note]EC statement on the issue calling for proper launch of the system: eeas.europa.eu/delegations/ukraine/press_corner/all_news/news/2016/2016_08_17_en.htm[/note] came out to defend the system. At the end of October 2016, about 120,000 officials submitted very detailed declarations of their incomes, assets, and property, as well as those of their families. The public was outraged by millions of dollars in cash declared by some. The NABU announced having opened investigations in a few of the cases.

Reforms such as e-procurement, unification of gas prices, deregulation, and the creation of new anti-corruption bodies would not have been possible without international support.

Adopting an e-declarations system was a requirement for getting a visa-free travel regime with the EU, as was the establishment of the National Agency for Recovery and Management of Illegally Received Assets, which is now recruiting staff.

The law “On the State Investigation Bureau” was passed at the end of 2015, and the Bureau is currently recruiting. These specialized bodies are a necessary part of anti-corruption reform. The only missing element is a specialized anti-corruption court.[note]Bohdan Vitvitsky, “Needed to Enforce Anti-Corruption Laws in Ukraine: Special Detectives, Special Prosecutors and Special Judges,” VoxUkraine, 9 October 2015. [/note]

A law addressing political corruption was adopted in fall 2015. On July 1, 2016, political parties published their declarations, which are mostly empty because the NACP cannot yet effectively enforce the law.[note]Andriy Kulykov, Natalia Sokolenko, Vita Dumanska,“In their Accounting Reports, Many Parties Wrote Zeroes – Dumanska,” Hromadske Radio, 8 August 2016.[/note] Another important draft law on whistleblower protection has been introduced in Parliament.[note] The full text of the law can be found at w1.c1.rada.gov.ua/pls/zweb2/webproc4_1?pf3511=59836[/note]

Reforms such as e-procurement, unification of gas prices, deregulation, and the creation of new anti-corruption bodies would not have been possible without international support. Specifically, all of these were included in the conditions of the IMF program, in order to overcome resistance by influential businessmen (oligarchs) and politicians.

The technical and financial assistance of international governments and NGOs cannot be underestimated. Under the IMF program, Ukraine received three tranches, but the third one has been delayed for more than a year, waiting until Ukraine fulfills the program conditions.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The two entities with the highest interest in the success of Ukrainian reforms are civil society organizations (CSOs) and international donors. Their cooperation should continue. In particular, the Ukraine Freedom Support Act of 2014[note]H.R. 5859, 113th Cong., 3 January 2014.[/note] authorises $20 million of assistance to civil society in Ukraine in 2016 (section 7, subsection d). The Act states that

“Not later than 60 days after the date of the enactment of this Act, the President shall submit a strategy to carry out the activities described in paragraph (1) to (A) the Committee on Foreign Relations and the Committee on Appropriations of the Senate; and (B) the Committee on Foreign Affairs and the Committee on Appropriations of the House of Representatives.”

The deadline expired a long time ago but the President has not submitted the strategy. Congress should continue to encourage the President to send the House Foreign Affairs Committee and Senate Foreign Relations Committee the required strategy, and to ensure that this section of the Ukraine Freedom Support Act receives the authorized funding through the appropriations process. Specific guidelines for effective support of anti-corruption CSOs are provided in the study Incentives and constraints for Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) to effectively engage in anti-corruption reforms at national and regional levels, performed by Pact and VoxUkraine and supported by USAID.[note]Tetyana Tyshchuk, “VoxUkraine Research. The Power of People: What Helps and What Prevents Civil Society Organizations from Combatting Corruption in Ukraine,” VoxUkraine, 15 September 2016.[/note]

Civil society has two main instruments to influence anti-corruption efforts: media activity and street action. In addition, civil society organizations often draft laws themselves, which are then passed with the help of the civil activists elected to Parliament in 2014. The arsenal of the international community includes “carrots,” i.e., financial and technical assistance, which should be strictly conditioned on the implementation of liberal reforms and anti-corruption measures. The international toolkit also contains “sticks” — such as personally sanctioning corrupt officials or tracing illegally obtained overseas assets of Ukrainian origin.

To increase the efficiency of the joint effort of Ukrainian civil society organizations and the international community, the U.S. should focus on encouraging Ukraine to pursue three key priorities aimed at dismantling the system of corruption:

- Narrowing the ground for corruption by continuing deregulation, SOE reform, and privatization;[note]One possible idea can be outsourcing privatization to an international fund. See, for example, Luc Vancraen, “Outsourcing Privatization In Ukraine To Attract Capital And Raise Efficiency,” VoxUkraine, 23 January 2015.[/note]

- Prosecuting current officials for their lack of integrity. This effort should be based on continuing the judicial reform process, reforming the law enforcement system by limiting the powers of the Prosecution office, creating efficient and effective anti-corruption bodies and anti-corruption courts, and managing the system of income/wealth e-declarations.

- Increase accountability of current officials by strengthening the involvement of businesses in the anti-corruption effort (e.g., by adopting legislation punishing “supply-side” corruption)[note]See, for example, Anton Marchuk, “Stick and Carrot: How to Interest Business in Fighting Corruption,” VoxUkraine, 20 July 2016.[/note], strengthening the involvement of citizens in anti-corruption efforts[note]See, for example, Keith Darden, “How to fight corruption: Time for qui tam laws?” VoxUkraine, 26 September 2014.[/note], and adopting laws on whistleblower protection.

The U.S. Congress and international organizations such as IMF or the World Bank should provide strong political support and, where appropriate, technical assistance to help with the implementation of the above priorities.

Keeping in mind that prevention is more important than punishment, it would be good to construct a bargain in which the adoption of reforms and dismantling of rent-seeking schemes is exchanged for the personal safety of corrupt officials, perhaps through a dual-track approach[note]See, for example, Gerard Roland, Yuriy Gorodnichenko, “Dual-Track for Ukraine: How to Fight Corruption,” VoxUkraine, 10 March 2015. [/note] or the adoption of some form of asset amnesty.

[wc_share_buttons class=””][/wc_share_buttons]

The views above are those of the author.