“Don’t call me a poet, because the term ‘poet’, in short, nowadays means: chameleon, prostitute, speculator, and adventurer, and a lazy good-for-nothing. I want to be a human being of whom there are but a few in the world.”

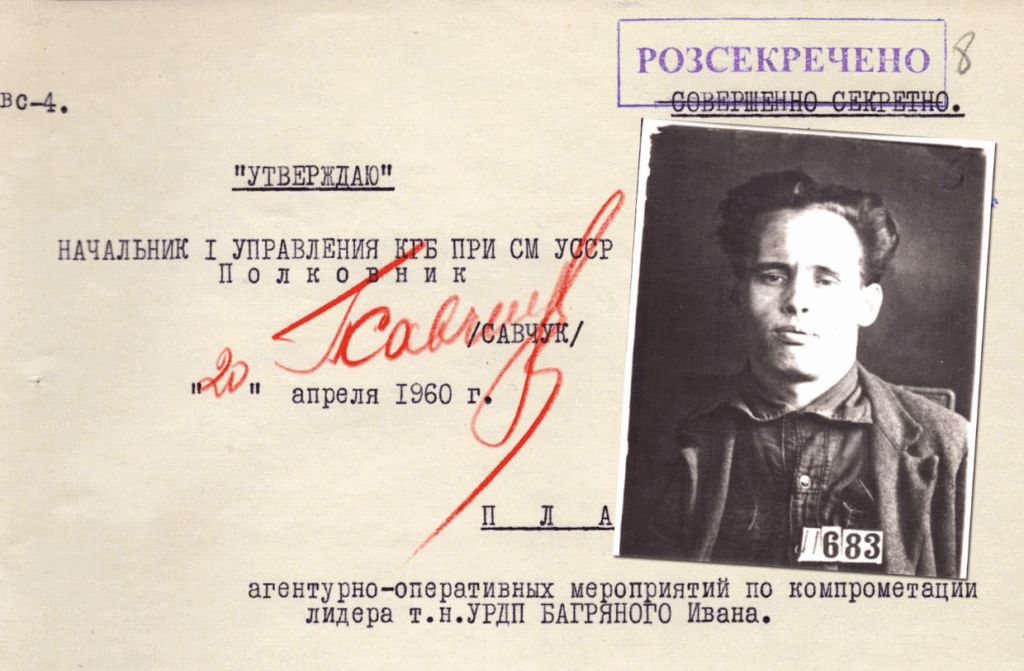

These poignant words, along with the rest of poetry written by Ukrainian writer Ivan Bahryanyi in his collection “To the Forbidden Frontiers” in the early 1930s, became grounds for labeling him the enemy of the Soviet state and sending him to a forced labor camp in Siberia – a destiny that befell many Ukrainian writers who dared to express any views that did not align with those of the Communist Party. The Soviet leadership understood very well what expression of dissent and criticism could mean for the longevity of the regime.

Tragically, this practice is inherited by the Russian Federation, which silences internal voices of dissent – while at the same time continuing the suppression of Ukrainian thought and writing that spans generations. The ongoing attack on Ukrainian museums, libraries, and book printers makes the support of Ukrainian literature an important tool of resistance and preserving national identity. Various Moscow-based regimes used language as a power tool that, over the course of several centuries, tried to erode the very essence of the Ukrainian nation. In 1769 The Moscow Synod banned the publication of Ukrainian primers and ordered the confiscation of existing ones. Later, in 1784, the imperial authorities banned Ukrainian lectures at the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy, and established Russian as the official language in all imperial schools. The 1863 Valuev Circular banned nearly all Ukrainian-language materials, claiming that “there never was, is not, and cannot be any separate little Russian language” and the subsequent 1876 Ems Ukaz extended the ban to prohibiting the import of Ukrainian books and the use of Ukrainian in public performances and musical notation. In the tragic 1930s, the Stalinist regime executed close to 30,000 Ukrainian intellectuals, a tragedy we now know as the Executed Renaissance. The many more insidious ways in which the Soviet leadership tried to erase Ukrainian language and identity are brought to light in “Language is a Sword. As the Soviet Empire Used to Say” by Evgenia Kuznetsova.

This understanding was reflected even in the treatment of prisoners at the forced labor camp, which Ivan Bahryanyi recounted in his statement during the hearing of the Committee on Un-American activities in the 86th Session of Congress in 1959: “Sadly, there was a marked difference in the treatment of political and criminal prisoners. Ordinary criminals and thieves were given light assignments, I mean, not heavy work, and they were known as not socially dangerous. The political prisoners were considered dangerous. Political prisoners, even if they complete the term of exile, are usually given a longer term, while ordinary prisoners sometimes have their term reduced.”

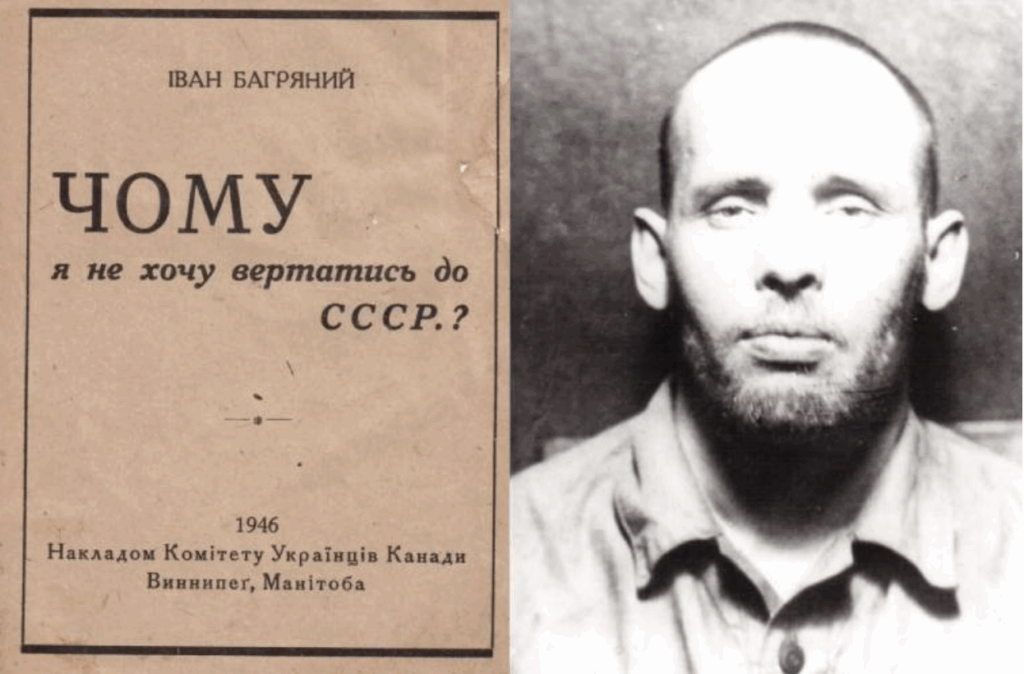

For most writers in the Soviet Union, there were only two pathways available: submit to the regime (and become a “chameleon” as Bahryanyi calls them in the quote above) or try to escape the grasp of the Party. Ivan Bahryanyi chose the second: “So I escaped at the end of 1936. I lived illegally without any passport or documents in the Soviet Far East, and then I returned – also illegally – to Ukraine. It was comparatively easy for me to live illegally in the Far East, because I lived among the people who sympathized with political prisoners and escapees, and I took part in the hunting for wild animals. As a result of this experience I later wrote a book which was published in English, in America, as “The Hunters and the Hunted.”

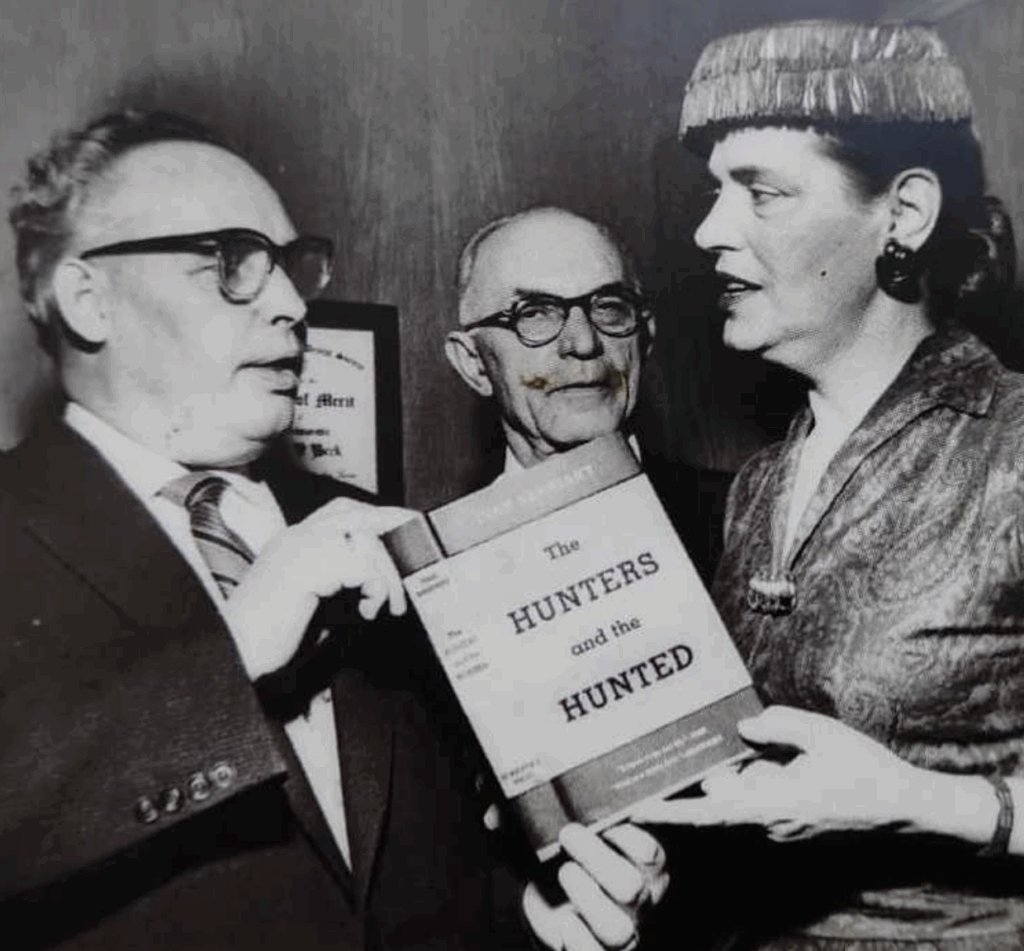

Based on the author’s own lived experience, “The Hunters and the Hunted” follows a young political prisoner Gregory Mnohohrishny who escapes a train bound for a forced labor camp and finds refuge with a family of tiger hunters in the Far East. The story explores the horrors of Stalinist repressions, the freedom sought by political prisoners, and the spark of defiance that overcomes fear.

Razom Connect is proud to support a stage reading of “The Hunters and the Hunted” musical based on Ivan Bahryanyi book at the Open Jar Studios in New York on May 29, 2025. This Ukrainian musical, co-written and co-composed by Anton Humaniuk, Bohdan Reshetilov, and Kyrylo Beskorovainyi, weaves history and contemporary events, celebrating Ukraine’s cultural heritage while examining the struggle between oppression and freedom. Directed by Lisa Rafferty, the reading will feature 11 songs (translated into English) and excerpts of dialogue, accompanied by a live piano performance by Ukrainian pianist Ruslan Ramazanov.

The international premiere of the musical took place at Harvard, and bringing the musical to a wider audience in New York, as a way to dismantle decades of Soviet – and now Russian – cultural propaganda through exhibits and exchanges – is something that Ivan Bahryanyi would himself approve of: “I think that the so-called cultural exchanges and exhibits have many dangerous features which Western nations, including the United States, do not realize. One of the most important purposes of these exchanges is to demoralize the Western countries, including the United States of America. It would be interesting for many Americans to know that these Soviet exchanges and exhibits portray, here in America and in many other countries, things which do not exist in the Soviet Union. The Soviet authorities endeavor to convince the world that they have such attainments in the art, in ballet, in music, and in other branches of culture because there exist cultural freedom in the USSR. In reality there is none such because there is no cultural freedom at all. Furthermore, this cultural exchange covers up the actual suppression of the national cultures of the many peoples in the Soviet Union. Why at this time, when when they show attainment of the Soviet State in the literary and artistic fields, at this very moment, are they suppressing the cultures of Ukrainians, Georgians, Armenians – and Byelorussians – and the Baltic peoples, who have no freedom to develop their own culture. They hide the Russification program which is even more dangerous for the free world, inasmuch as Moscow is perpetuating a vast spiritual genocide against the many peoples it controls.”

Support of this stage reading is one of the many initiatives of Razom Connect to promote Ukrainian literature in the English speaking world. Developing relationships with publishers, translators, booksellers allows Razom to support translations of such books as “Mondegreen” by Volodymyr Rafeyenko, “Cecil the lion Had to Die” by Olena Stiazhkina, “My Woman” by Yulia Iliyukha, and “Amadoka” by Sophia Andrukhovych. In 2024 alone, the team of Razom Connect organized eight literary events in New York, and coordinated a U.S. book tour for five Ukrainian authors.

The importance of this work is hard to overstate – it helps bring Ukrainian voices to the forefront of conversation about historic truth – and better understand the underpinnings of the current full-scale invasion of Ukraine. When Richard Arens, Staff Director at the U.S. House of Representatives, asked Ivan Bahryanyi during the Congressional hearing: “Why do the Soviets persecute poets, writers, or other literary persons more than they do ordinary criminals?”, the author responded: “The Soviet regime considers the ordinary criminals, when they commit a crime, damage or harm to a single person or individual, whereas poets, writers, literary figures, when they are anti-Soviet, naturally damage the entire Soviet system, the foundation on which it stands, because through the literature they spread a different kind of ideology, different kinds of beliefs, than those in which the communists believe.”

To anyone who has ever paid attention in history class, the importance of language for identity and nation-building is crystal clear. From the Stoic teachings of Marcus Aurelius that still resonate today, to the ideas of Enlightenment that sparked the French Revolution, and to the “I Have a Dream” speech by Martin Luther King, Jr., the power of words to shape consciousness and steer history is hard to overstate. Time has also shown the ability of language to break down, destroy, and dominate – the novel “1984” by George Orwell being one of the classic examples. Orwell’s work explores how use of language as a tool of control (through “Newspeak”) and the loss of objective truth (“doublethink”) can suppress dissent, erase privacy, and dominate the minds and lives of citizens.

Please help Razom bring more literary events, readings, and publications from and about Ukraine to the English speaking world. Donate to the program below – and stay tuned for more announcements of exciting and meaningful initiatives.